Essay

Sojourns in the realm of the unreal

by Louis Ho

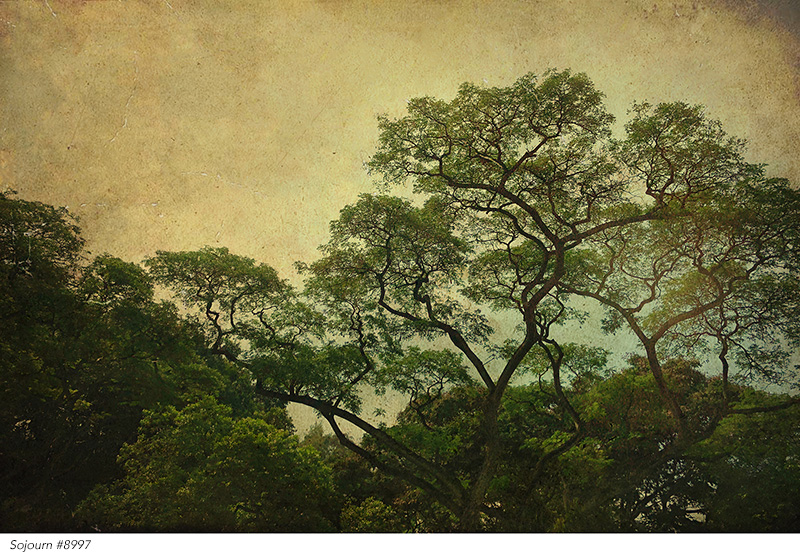

Sojourn #8997 is a tranquil image of a treescape, a carefully calibrated gaze at the webbed, filigree-fine spread of a rain tree (Samanea saman), radiating out over a backdrop of foliage into the pale ochre of a crepuscular sky. In similar fashion, Sojourn #3025 and #1894 are oneiric vistas of seemingly tropical terrain. The former sports a pair of coconut trees, their tips jutting out into a rolling sweep of baby blue and blush pink clouds overhead, while the latter features a single lofty, spindly palm - perhaps the wax palm, or Ceroxylon quindiuense - poised enigmatically against a clear, cerulean firmament. Unlike its fellows, Sojourn #3025 proffers a study of a cumulus cloud, an expressively chiaroscuric portrait that recalls the richly detailed skies of a landscape painting.

What the aforementioned pictures have in common, however, are their tones and textures: a grainy, velvety finish coats each individual tableau almost in the manner of the scratched, spoiled surface of an old photograph, the muted palette of the image evoking the soft wash of shades associated with hoary camera techniques, a testament, perhaps, to the aesthetic sensibility of what the Japanese refer to as wabi-sabi, an appreciation of the natural processes of weathering, erosion and breaking down.

Yet, the suite of images that constitutes Jeannie Ho’s Sojourn series is anything but natural. They are, rather, decidedly un-natural representations of natural topographies, hybrid objects embedded in layers of subterfuge, caught in the constantly shifting lines between authenticity and artifice and, more essentially, in the ontological interstices between photography and painting, their categorization as either genre of artefact lost in a play of visual manipulation. These crossbred pictures originate in methodically “banal” and “lo-tech” photographs of landscapes, as the artist puts it, that she encountered in the course of her daily activities. They are snapshots of green spaces around Singapore that occurred often during her commutes, glimpsed along roads and highways rather than sought out in the few areas of wilderness remaining on the island, and captured with her phone or a pocket digital camera. Her subsequent manipulation of these quotidian pictures are intended to convey a certain mood and visual effect. The original photos are layered with other images of textured surfaces, ranging from damaged walls to grazed cookware, to achieve the surficial aspect of tactile, granular materiality. The images are then further engineered, with the aid of editing programs, to produce the desired painterly aesthetics, from ethereal chromatics to heightened chiaroscuro, as if the final product had technologically retrogressed from digital insubstantiality to physical objecthood.

It is the allusion to Western pastoral painting traditions that provides a vital context for Ho’s pictorial manoeuvers, complicating the so-dubbed banality of the photographs, which in their original incarnations evoke, perhaps, what filmmaker and artist Hito Steyerl refers to as the poor image, “a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image.”1 Ho was trained as a painter during her early days in art school, and, in fact, recalls a personal anecdote about childhood acquaintance with styles of Western visuality:

.. early painting styles were an influence even before I went to art school, probably because of some random (not very good) landscape paintings vaguely reminiscent of 19th-century masters in my grandfather’s living room where I spent a lot of alone time in my very early childhood. I remember sitting alone on quiet afternoons, staring at a forest scene of one of the paintings, wondering if I stared hard enough maybe I could see what’s in the soft fuzzy dark background beyond the layers and layers of trees.

Perhaps that early inquisitive gaze, focused on the “soft fuzzy background” of what was likely a mass-produced version of a Western landscape - not unlike Steyerl’s poor image - frames the ambience and textures of the Sojourn series. Here, it has been transmuted into rich, intertextual images, enhanced by a canny referentiality. The cloud study of #3025 harkens back to a long tradition, particularly in Dutch and Flemish landscape painting, that saw the emergence of clouds as a subject of artistic study in their own right. Jacob van Ruisdael’s work is noted in this regard, as is that of the English painter John Constable, whose cloud studies were as much expressions of personal sentiment as they were depictions of the celestial environment, described by a critic as “a series of Romantic lyrics: exhalations and exclamations, meditations and reflections, attached to a specific location and moment in time.”2 Elsewhere, the artist has compared #8997 to the landscapes of Claude Lorrain and Charles-François Daubigny, with the former’s hazy, atmospheric perspective, mellow tonalities and general aura of placid calm, in particular, informing Ho’s own edited images. It is the arboreal motif that connects Lorrain’s visual universe most conspicuously with hers, with the sight of a spreading crown soaring into the skies, elevated above an arcadian vista, a salient nod to the French painter.

The evocation of pastoral painting traditions that seemingly bear little contextual relevance to Singapore in the twenty-first century, their place in the scheme of things here owed instead to the artist’s particular predilections, attest to the fact that the Sojourn works are deliberately deracinated objects. Ho avers that they are to be understood as pictures that are time-less and place-less, innominate portrayals of locales that are not transcriptions of, or pointers to, specific locations. While the photographs were all taken at various sites in Singapore, the artist observes that she did not depart from her usual routines to capture them. What the images set out to accomplish, rather, is a correspondence to the kernel of an idea or emotion that strikes her in the interlude between moment and moment, in the stream of consciousness that constitutes daily reality. They are intended to serve as visual analogues of passing perceptions that emerge from the mental flow, their preferred arrangement in a non-sequential layout, with varied sizes and orientations, a reinforcement of this phenomenon. She remarks: “The images, soundscapes, and moving stills are landscapes of unthinking and disremembering ... pausing, and collecting both micro-blinks of unthoughts, and instants of unexpected episodes of contemplation and reflection.” The catalogue of cognitive formations - reflections, micro-blinks, unthoughts, disremembering - dovetails, then, with the aesthetic gesture of inflecting the images to disrupt the objectivity of their visual record, foregrounding their inherent instability.

As has been pointed out, “a photograph can denote only something that exists at definite spatial and temporal coordinates in the physical world, so a photograph always tells us--as the footprint on the beach told Robinson Crusoe--that something was actually out there.”3 The documentary function of the camera, the corroboration that something was indeed actually out there, alludes to the scripting of the Sojourn works as ecological tableaux, witnesses to the extensive urbanization of Singapore’s terrain, and the confined, circumscribed islands of natural flora cast adrift in a sea of development - almost, in the artist’s words, as if “they are reminders of the origins of the earth, otherworldly and foreign, and unfamiliar to ... those who know Singapore.” Even more essentially, however, these pictures are photographs explicitly doctored to resemble paintings - nimbly, shrewdly negotiating the protean flux of shifting ontologies, oscillating between factual testimony and fictive reference and insistent in their eluding of determined identities and meaning. It is then perhaps only logical that they are subjective, intensely personal images, deriving significance from the otherwise hidden wellsprings of autobiography. The works, while foregrounding concerns regarding the natural environment are also, ultimately, suggestions of interior landscapes, emotional and mental terrain that is conveyed through the deliberate unreality of these topographies. They are, to quote Ho, “the space between places, the place between spaces, the liminal and peripheral spaces amidst the infinite transitions of monotonous structured thoughts".

Notes

1 The contours of the poor image, from its casual aesthetics to its universal accessibility and circuits of consumption, are laid out by Steyerl in her article, “In Defense of the Poor Image”. e-flux Journal #10, November 2009. Accessed January 30, 2021.

<https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/>

2 Mary Jacobus, Romantic Things: A Tree, a Rock, a Cloud (Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 2012), pp. 13-14.

3 William J. Mitchell, The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992), p. 195

Louis Ho is an independent curator, critic, and art historian, whose recent exhibitions include "The Foot Beneath the Flower: Camp. Kitsch. Art. Southeast Asia" at the NTU ADM Gallery in Singapore, and “Strange Things” at 2 Cavan Road. He was previously a curator at the Singapore Art Museum and was a co-curator of the Singapore Biennale 2016.